Using Television to Expose Racial Injustice

Filoli’s exhibition Stories of Resilience shares stories of the individuals and identity groups who overcame injustices or were historically excluded from performing at or working at Filoli.

Census records reveal that there were no Black staff at Filoli during its time as a family home. Though the African American population in the Bay Area boomed after the end of World War II, the Peninsula was not a welcoming place for Black families.

Despite its progressive reputation today, the Bay Area pioneered racially exclusive policies in housing in the 1950s and 1960s.

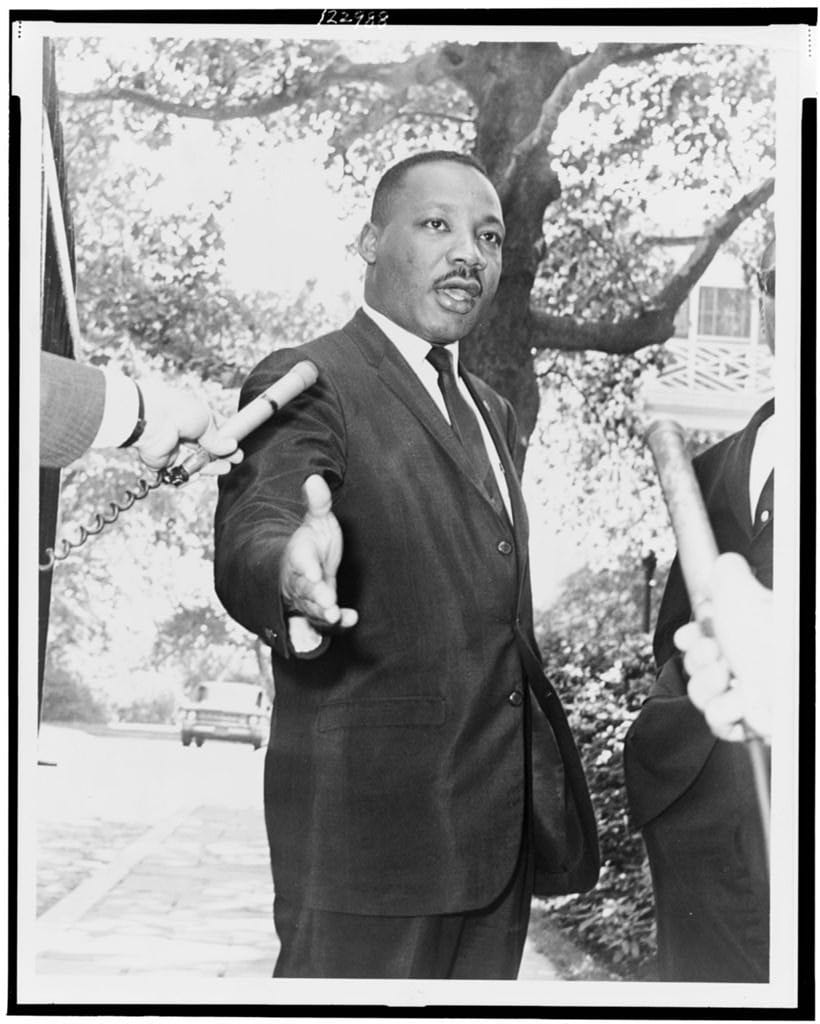

In Filoli’s Family Room, Bay Area news footage from the 1960s highlights the way Martin Luther King, Jr., used television coverage to expose racial injustice and advance the civil rights cause. His approach ensured that the faces of the movement and key events like the March on Washington and Selma protests were visible on television screens across America and the world.

Television news broadcasts began in the 1940s and expanded after the end of World War II. The industry hit its stride in the 1960s, when advances in portable camera equipment allowed reporters to broadcast live outside the studio. Television audiences exploded as well during this time: by 1962, 90 percent of American households owned a TV set.

On a typical 1960s evening, the Roth family sipped cocktails and played table games in the Family Room. On August 28, 1963, however, they might have watched live — on their 1962 Zenith television — as King delivered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. As 250,000 peaceful marchers walked from Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial, the major networks carried parts of the event live and people all over the nation tuned in. The march received unprecedented media attention, with about 3,000 members of the press covering it.

Three main networks (CBS, NBC, and ABC) dominated at the time, with affiliates in cities across the country delivering local news. San Francisco’s first TV station was KPIX, which debuted on air in December 1948. On the television in Filoli’s Family Room, we show KPIX footage of King speaking at a 1966 press conference about civil unrest, contrasted with the memorial rally held after his assassination at Civic Center Plaza. The event was covered by KPIX reporter Belva Davis — the first female African American news anchor on the West Coast.

King saw television as a way to influence public opinion on a national scale. He was savvy, attracting media attention through mass protests and charismatic oration. Even in death, King dominated the networks as TV coverage after his assassination captivated the nation.

Speaking after the brutal repression of protestors at the Selma to Montgomery march in 1965, King was upfront about his strategic emphasis on live coverage: “We are here to say to the white men that we no longer will let them use clubs on us in the dark corners. We’re going to make them do it in the glaring light of television.”

Blog by Willa Brock, Interpretation Manager